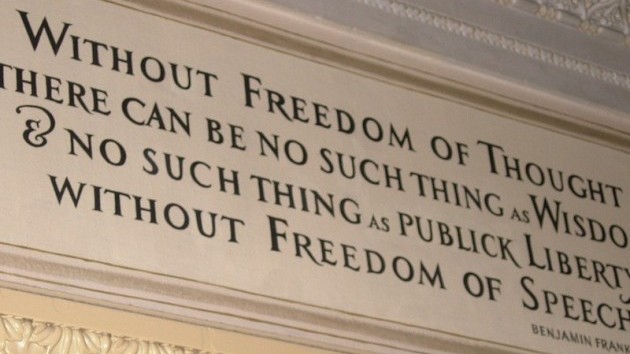

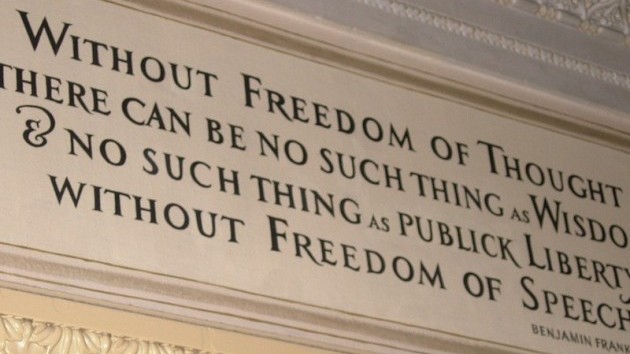

“Without Freedom of thought there can be no such thing as wisdom;and no such thing as public liberty, without freedom of speech.”

Thought police, in George Orwell’s dystopian 1949 work, “1984,” were government authorities tasked with rooting out thought crimes – or, the basic mental patterns that were believed to be the genesis for criminal actions – using omnipresent surveillance technologies and intelligence gathering techniques.

Supposedly, that was fiction.

Yet, PredPol is making quite a wave among law enforcement. So is crime mapping. So is AlSight. What are these? In short, technology that fits right in with Orwell’s narrative.

PredPol, short for Predictive Policing, is cloud-based software that takes police incident reports, sifts them through an algorithm and then spits out an analysis of where crimes are most likely to occur on a given shift – and which types of criminal activities are probably going to take place in a given hour. The logic is that officers reporting for their shifts can then use that data and conduct more common sense patrols.

As Los Angeles Police Chief Charlie Beck said: “I’m not going to get more money. I’m not going to get more cops. I have to be better at using what I have, and that’s what predictive policing is about.”

Crime mapping, meanwhile, pinpoints the geographical locations of various types of past criminal activities as a way of directing the path of police patrols for the present and future – a sort of intelligence-gathering system. A heavy drug crime area? Send in the drug task force members to conduct undercover buy operations. A rash of home burglaries in the neighborhood? Add extra patrol cars to that part of town.

AlSight, created by the Texas-based BRS Labs, is a bit different – and more Orwellian. This software works in conjunction with data captured on surveillance cameras to first, track and determine what constitutes normal behavior for the area of spy coverage – and second, alert and report those behaviors that step outside the parameters of what’s been determined as normal. The touted beauty of AlSight is that it can take on a human-type consciousness to compare and contrast what’s normal – travelers boarding a train, for example – versus what isn’t – a passenger dropping a bag by a trash barrel and walking away, for instance – and alert the authorities accordingly.

And all three programs are supposed to keep the nation safer – the communities freer of crime. Santa Cruz, Calif, reported a double-digit drop in its crime rate since implementing PredPol. Shreveport just became the second city in Louisiana to adopt crime mapping and call on citizens to help locate the suspect who stole a gun out of a police officer’s patrol car. San Fernando Valley reported substantial drops in burglaries since launching its predictive policing program in 2011. And AlSight has been a monitoring tool of choice for some time for San Francisco’s Municipal Transit Authority, for select spots in Houston, Texas, and for water treatment plants in El Paso.

But the technology brings some queasiness – and constitutional concerns.

Since when is the default operating mode for law enforcement to assume Americans are guilty? Isn’t that, in essence, what these programs, with their catch-all surveillance, and their computerized analytics, are doing – collecting data on citizens who’ve yet to be charged or even suspected of crimes, and then placing at least some of them under targeted police watch?

Innocent until proven guilty used to be the guiding law enforcement light in our republic. Thoughts are not actions – thoughts are never crimes.

Cherly Chumley, a full-time news writer with The Washington Times, is also the author of Police State USA: How Orwell’s Nightmare is Becoming Our Reality, available at Amazon and Barnes & Noble. To learn more about Cheryl, visit her website.

[mybooktable book=”police-state-usa-how-orwells-nightmare-is-becoming-our-reality” display=”summary”]