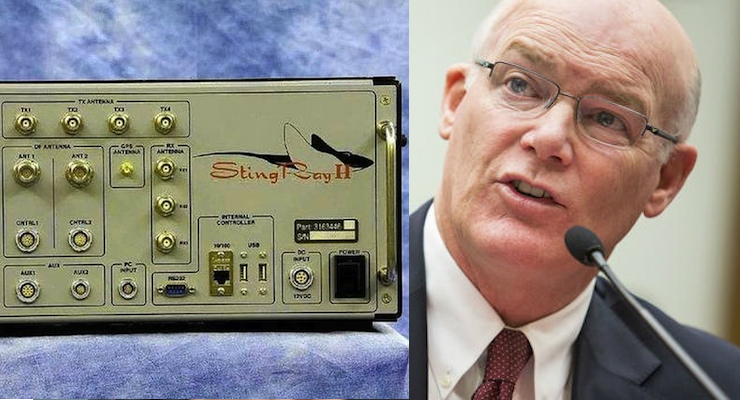

Joseph Clancy, acting director of the United States Secret Service, testifies during a House Judiciary Committee Hearing, right, and left, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office shows the StingRay II, manufactured by Harris Corporation, of Melbourne, Fla.

In between the brouhaha of Joe Biden’s stand-down from the presidency and Hillary Clinton’s staged stand-up to Benghazi-tied accusations by Congress, comes this, courtesy of the federal government: The Fourth Amendment, the one guaranteeing protections against unreasonable searches and seizures, is no longer in effect.

Or, in the words of the government’s appointed spokesman, Homeland Security assistant secretary Seth Stodder, in widely reported remarks: The Secret Service is now joining the Justice Department is claiming “exigent circumstances” to use cellphone tracking technology, i.e. Stingrays, without first obtaining warrants.

It’s just too dang time-consuming, he said. And the people who need protection, like the president, are just too important to subject to bothersome constitutional requirements.

He used fancier language, of course, while explaining just why federal law enforcement doesn’t need to abide the Constitution.

“The key exception that we envision is the Secret Service’s protective mission,” Stodder said, according to media reports. “In certain circumstances where you could have an immediate threat to the president and you have cryptic information, our conclusion in drawing the line between security and privacy here is to err on the side of protection.”

Well, isn’t that special.

In other words, the Secret Service mission — which is not only to protect the president, but also other high-ranking political officials deemed at-risk — is way more important than the preserving the integrity of our nation’s guiding legal document. They have to watch out for people who are way more important than the average American. And therefore, they get to circumvent laws that were put in place long ago, by Founding Fathers who wanted to prevent — get this — the very federal government from having the ability to intrude on citizens’ right to be secure in their persons and possessions, absent a judge-sanctioned warrant.

Stingrays, for those in the dark, are signaling devices originally developed for the military and now commonly used by civilian law enforcement agencies that capture cell phone data. They don’t tap into conversations or text messages, but they do alert to the identity and location of the cell phone holder — and that includes the holders of all the cell phones in the range of the Stingray.

Translation: Stingrays scoop up data on suspects and non-suspects alike. That means said scoopers are gathering private information on American citizens who aren’t even accused or suspected of doing anything wrong, absent court warrant. Isn’t this exactly what the Fourth Amendment is supposed to prevent?

Why yes. Why yes, it is.

And yet, we’re here: The Secret Service’s new policy is to allow an agent to cite “exceptional circumstances” to an “executive-level” dude within his or her own agency or at a U.S. attorney’s office, who can then sign an OK for the law enforcement official to use the Stingray tracking technology. That’s according to Stodder, who emphasized the federal government would only use the data in extreme circumstances, not simply routine criminal investigations.

We’re from the government – you can trust us, he says.

It’s for the sake of “protection” and security, he says.

It seems prudent at this point to quote Ben Franklin, and his works of wisdom about those who trade liberty for temporary safety “deserve neither liberty nor safety.”

It also seems judicious to wonder about this: If the supposed security of some is the standard by which we gauge the sensibility of the Constitution, how long will the Fourth Amendment last?

The answer’s clear – not long. Little by little, chip by chip, constitutional rights are being whittled, almost always for the reason of safety and security. At the same time, Americans are slowly being conditioned to buy into the well-worn, weary government sneak logic that we’re all worthy of protection – just some, much more than others.

[mybooktable book=”police-state-usa-how-orwells-nightmare-is-becoming-our-reality” display=”summary” buybutton_shadowbox=”true”]