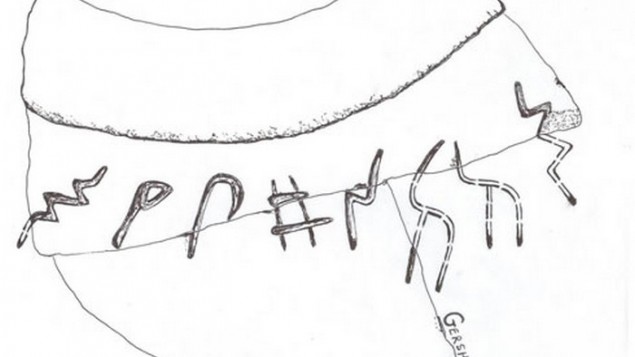

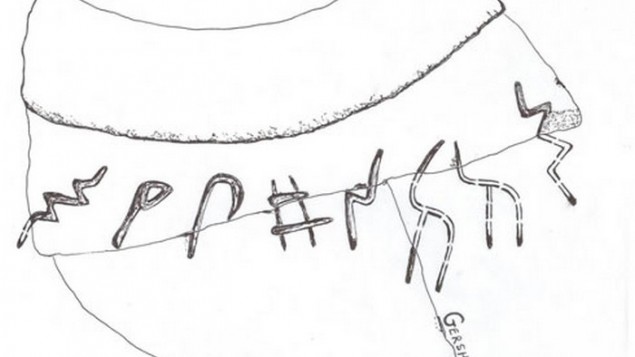

The engraving found on a 3,000-year-old clay jug is Jerusalem’s oldest inscription. (Photo: “New Studies on Jerusalem” Journal)

Biblical scholar Gershon Galil from the Bible Department at the University of Haifa says he has decoded Jerusalem’s oldest inscription dating back to the reign of King Solomon around 3,000 years ago.

The ancient 8-letter inscription was discovered on a clay jug near Ophel, which is located close to the southern wall of the Temple Mount, by a Hebrew University archaeological team headed up by Dr. Eilat Mazar.

In the Hebrew journal “New Studies on Jerusalem,” Galil wrote he believes the 8 letters, which were first thought not to be written in Hebrew, were in fact in early Hebrew and included the word for wine, or “yayin.” Also, according to Galil, the first intact letter observed on the inscription was actually the last letter of a longer word that was cut off, which represents the date. The middle portion of the carving refers to the type of wine stored in the jug — a “lowly” or cheap wine.

Galil claims the final letter originally carved on the inscription was also cut off from a longer word and identifies the location the wine was sent from.

Galil estimated that the carving was written in the middle of the tenth century BCE, which is after the period King Solomon built the First Temple, his palaces, and the massive surrounding walls that connect the 3 areas of the city — the Ophel area, the city of David, and the Temple Mount.

Though it may sound insignificant, the translation is a revelation, because archaeologists believe that infrastructural projects contributed, in large measure, to the need for large quantities of poor-quality wine.

“This wine was not served on the table of King Solomon nor in the Temple,” Galil wrote. “Rather it was probably used by the many forced laborers in the building projects and the soldiers that guarded them. Food and drinks for these laborers were mainly held in the Ophel area.” Galil’s theory is strengthened by other discoveries, including pottery fragments found in Arad.

“The ability to write and store the wine in a large vessel designated for this purpose, while noting the type of wine, the date it was received, and the place it was sent from, attests to the existence of an organized administration that collected taxes, recruited laborers, brought them to Jerusalem, and took care to give them food and water,” Galil wrote.

“Scribes that could write administrative texts could also write literary and historiographic texts, and this has very important implications for the study of the Bible and understanding the history of Israel in the biblical period.”

As has become typical of biblical discoveries, so-called mainstream archeologists are already gearing up to challenge some of the findings published by Galil. If Galil is correct, then the findings fly in the face of what has been a known concerted effort over decades by some “mainstream” scholars to reduce the historical account found in the Bible to little more than fairytale.

Despite the account written in the Bible and supporting archeological evidence, many claim the Hebrew nation was not as sophisticated or elaborate as the Bible suggests, and certainly not as Galil emphasized, which is what we would recognize as an organized bureaucratic system.

“Galil’s interpretation is sure to add fuel to the archaeological fires regarding the magnitude of David and Solomon’s kingdom,” Haaretz wrote.

“Some archaeologists believe that Jerusalem was a small, unimportant town, contrary to its biblical description. Galil and others view the Bible as a reliable historical document. For them, the inscription is proof of a significant, well-administered kingdom that received goods from afar and expanded during Solomon’s time from the City of David toward the Temple Mount.”