NASA’s Kepler space telescope team has identified 219 new planet candidates, 10 of which are near-Earth size and in the habitable zone of their star. (Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The NASA Kepler space telescope team released a mission catalog including 10 near-Earth size planets orbiting within their star’s habitable zone, or Goldilocks Zone. The planet candidates were introduced with 209 others, but those are located far enough from a star where liquid water could pool on the surface of a rocky planet.

“The Kepler data set is unique, as it is the only one containing a population of these near Earth-analogs – planets with roughly the same size and orbit as Earth,” said Mario Perez, Kepler program scientist in the Astrophysics Division of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “Understanding their frequency in the galaxy will help inform the design of future NASA missions to directly image another Earth.”

The findings were presented at a news conference Monday at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley. The Kepler space telescope searches the sky for planets by detecting a “minuscule” dimming in a star’s brightness that occurs when a planet crosses in front of it, which is known as a transit.

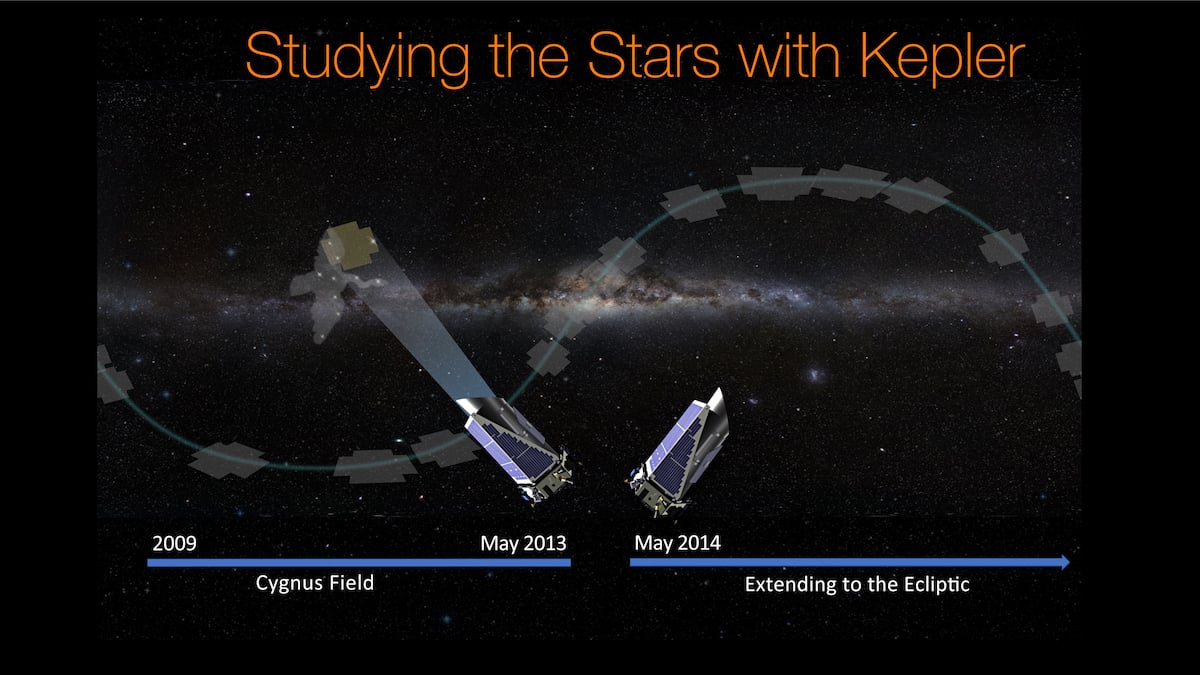

NASA’s Kepler space telescope was the first agency mission capable of detecting Earth-size planets using the transit method, a photometric technique that measures the minuscule dimming of starlight as a planet passes in front of its host star. For the first four years of its primary mission, the space telescope observed a set starfield located in the constellation Cygnus (left). New results released from Kepler data June 19, 2017, have implications for understanding the frequency of different types of planets in our galaxy and the way planets are formed. Since 2014, Kepler has been collecting data on its second mission, observing fields on the plane of the ecliptic of our galaxy (right). (Photo Credit: NASA/Wendy Stenzel)

In February, NASA also announced the discovery of 7 Earth-like planets orbiting a star some 40 light years away, including 3 planets in the Goldilocks zone. The zone refers to a “not too hot, not too cold” distance planets orbit from their star making them potentially habitable environments for life.

“This carefully-measured catalog is the foundation for directly answering one of astronomy’s most compelling questions – how many planets like our Earth are in the galaxy?” said Susan Thompson, Kepler research scientist for the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California, and lead author of the catalog study.

Interestingly, a research group at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii using data collected by Kepler was able to take precise measurements of thousands of planets, which discovered two groups of small planets. The team found a clear grouping in the sizes of Earth-size rocky planets and gaseous planets smaller than Neptune. Few planets were found between those groupings.

The group precisely measured the sizes of 1,300 stars in the Kepler field of view to determine the radii of 2,000 Kepler planets.

“We like to think of this study as classifying planets in the same way that biologists identify new species of animals,” said Benjamin Fulton, doctoral candidate at the University of Hawaii in Manoa, and lead author of the second study. “Finding two distinct groups of exoplanets is like discovering mammals and lizards make up distinct branches of a family tree.”