Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras speaks with the media after a meeting of eurozone heads of state at the EU Council building in Brussels on Monday, July 13, 2015. A summit of eurozone leaders reached a tentative agreement with Greece on Monday for a bailout program that includes “serious reforms” and aid, removing an immediate threat that Greece could collapse financially and leave the euro. (AP Photo/Geert Vanden Wijngaert)

Changing demographics is one of the most powerful arguments for genuine entitlement reform. When programs such as Social Security and Medicare (and equivalent systems in other nations) were first created, there were lots of young people and comparatively few old people.

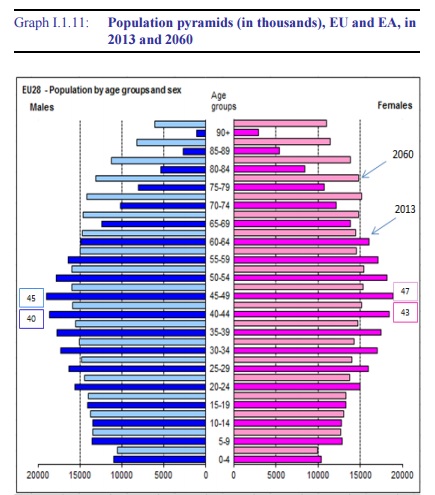

And so long as a “population pyramid” was the norm, reasonably sized welfare states were sustainable (though still not desirable because of the impact on labor supply, savings rates, tax policy, etc).

In most parts of the world, however,demographic profiles have changed. Because of longer life expectancy and falling birth rates, population pyramids are turning into population cylinders.

In most parts of the world, however,demographic profiles have changed. Because of longer life expectancy and falling birth rates, population pyramids are turning into population cylinders.

This is one of the reasons why there is a fiscal crisis in Southern European nations such as Greece. And there’s little reason for optimismsince the budgetary outlook will get worse in those countries as their versions of baby-boom generations move into full retirement.

But while Southern Europe already has been hit, and while the long-run challenge in Northern European nations such as France has received a lot of attention, there’s been inadequate focus on the problem in Eastern Europe.

The fact that there’s a major problem surprises some people. After all, isn’t the welfare state smaller in these countries? Haven’t many of them adopted pro-growth reforms such as the flat tax? Isn’t Eastern Europe a success story considering that the region was enslaved by communism for many decades?

To some degree, the answer to those questions is yes. But there are two big challenges for the region.

First, while the fiscal burden of government may not be as high in some Eastern European countries as it is elsewhere on the continent (damning with faint praise), those nations tend to rank lower for other factors that determine overall economic freedom, such as regulation and the rule of law.

Looking at the most-recent edition of Economic Freedom of the World, there are nine Western European nations among the top 30 countries: Switzerland (#4), Ireland (#8), United Kingdom (#10), Finland (#19), Denmark (#22), Luxembourg (#27), Norway (#27), Germany (#29), and the Netherlands (#30).

For Eastern Europe, by contrast, the only representatives are Romania (#17), Lithuania (#19), and Estonia (#22).

Second, Eastern Europe has a giant demographic challenge.

Here’s what was recently reported by the Financial Times.

Eastern Europe’s population is shrinking like no other regional population in modern history. …a population drop throughout a whole region and over decades has never been observed in the world since the 1950s with the exception of…Eastern Europe over the last 25 consecutive years.

Here’s the chart that accompanied the article. It shows the population change over five-year periods, starting in 1955. Eastern Europe (circled in the lower right) is suffering a population hemorrhage.

By the way, it’s not like the trend is about to change.

If you look at global fertility data, these nations all rank near the bottom. And they also suffer from brain drain since a very smart person, even from fast-growing, low-tax Estonia, generally can enjoy more after-tax income by moving to an already-rich nation such as Switzerland or the United Kingdom.

So what’s the moral of the story? What lessons can be learned?

There are actually three answers, only two of which are practical.

- First, Eastern European nations can somehow boost birthrates. But nobody knows how to coerce or bribe people to have more children.

- Second, Eastern European nations can engage in more reform to improve overall economic liberty and thus boost growth rates.

- Third, Eastern European nations can copy Hong Kong and Singapore (both very near the bottom for fertility) by setting up private retirement systems.

The second option obviously is good, and presumably would reduce – and perhaps ultimately reverse – the brain drain.

But the third option is the one that’s absolutely required.

The good news is that there’s been some movement in that direction. But the bad news is that reform has taken place only in some nations, and usually only partial privatization, and in some cases (like Poland and Hungary) the reforms have been reversed.

And even if full pension reform is adopted, there’s still the harder-to-solve issue of government-run healthcare.

Eastern Europe has a very grim future.

P.S. I’m a great fan of the reforms that have been adopted in some of the nations in Eastern Europe, but none of them are small-government jurisdictions. Yes, the welfare state in Eastern European countries is generally smaller than in Western European nations, but it’s worth noting that every Eastern European nation in the OECD (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia) has a larger burden of government spending than the United States.

[mybooktable book=”global-tax-revolution-the-rise-of-tax-competition-and-the-battle-to-defend-it” display=”summary” buybutton_shadowbox=”true”]