North Korean leader Kim Jong Un inspects the intercontinental ballistic missile Hwasong-14 in this undated photo released by North Korea’s Korean Central News Agency (KCNA) in Pyongyang July 5, 2017. (Photo: Reuters/KCNA)

North Korea’s new Hwasong-14 is an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) capable of hitting the United States (US) mainland. Here’s an in-depth analysis of the background, design development and capabilities of the Hwasong-14.

Background

On July 4, North Korea conducted its first success test of the Hwasong-14. People’s Pundit Daily, citing U.S. Pentagon officials, reported almost immediately that it was “something new.” It flew for 37 minutes and reached a height of more than 1,500 miles, or at an altitude of 2,803 kilometers (km), breaking the DPRK’s previous record set on Mother’s Day.

Based on that test, it was initially believed that the Hwasong-14 could potentially reach up to 8,000 kilometers if fired rotating it in an easterly direction. The U.S. government assessed the range from 7,000 km to 9,500 km.

On July 28, North Korea conducted its second successful test of the Hwasong-14. The launch was believed to be scheduled for Thursday, the 64th anniversary of the signing of the armistice that ended fighting in the Korean War.

It outperformed the test on July 4, flying for roughly 45 minutes to a range of about 1,000 km and to an altitude of roughly 3,700 km. Based on the data, the Hwasong-14 could potentially have a range of more than 10,000 km if rotated to fly on a range-maximizing ballistic trajectory.

Capabilities

The second test demonstrated the Hwasong-14 has the capability to reach the U.S. mainland. In fact, its range is far enough to reach the vast majority of the Continental United States (CONUS).

The rotation of the Earth provides somewhat of a slingshot boost to ICBMs, increasing their range when traveling eastward. When factoring in this rotation, the Hwasong-14’s coverage area would include the West Coast, Chicago, and potentially even New York.

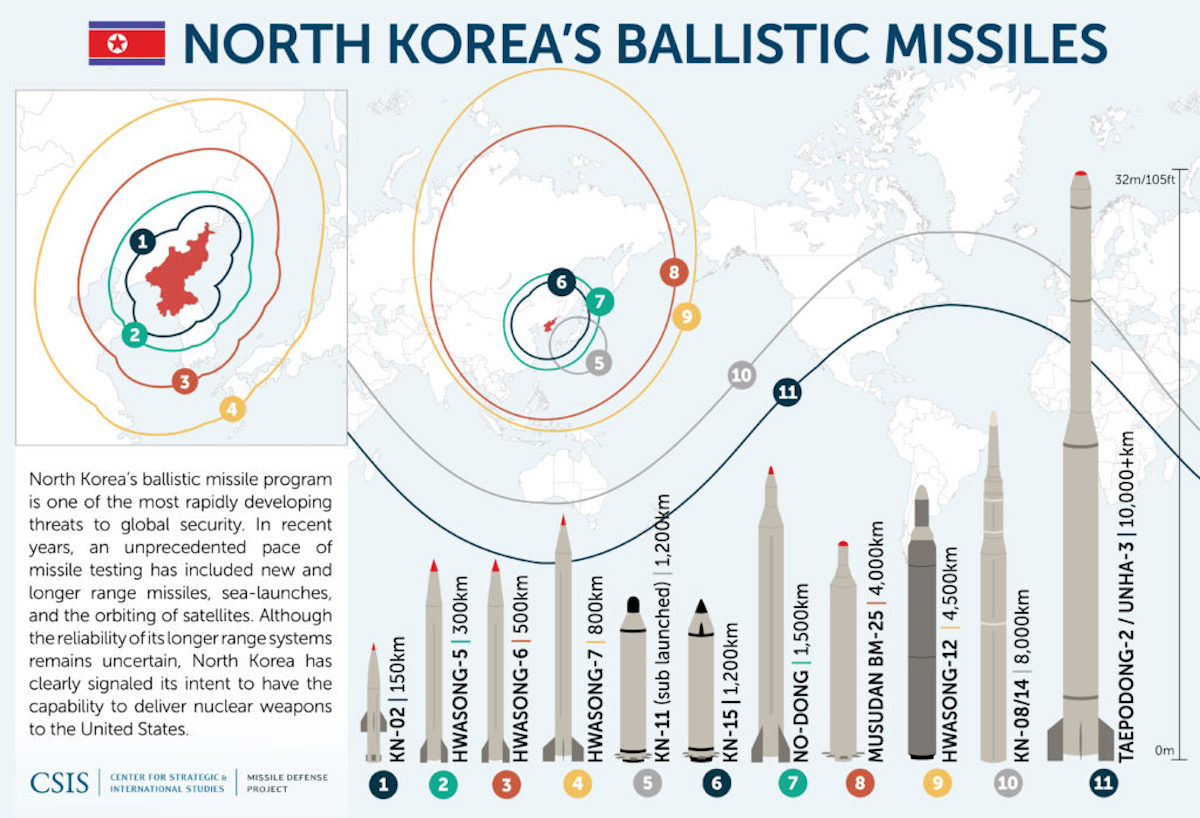

North Korean Missiles Capabilities (Source: CSIS)

Video footage taken from a rooftop by Japan’s NHK television on the northern island of Hokkaido indicates the Hwasong-14’s re-entry vehicle did not survive the extreme heat and/or pressure from re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere. U.S. missile expert Michael Elleman, who analyzed the footage, believes it “disintegrated” before it landed in the Sea of Japan.

Mr. Elleman said on a conference call that small radiant objects can be seen at an altitude of 2.5 to 3 miles but dim and quickly disappear at an altitude of 1.9 to 2.5 miles before it passes behind a mountain range. He noted that if the re-entry vehicle survived, it would have continued to glow until disappearing behind the mountains.

Design Development

Worthing noting first, when reading news reports, it’s important to understand that North Korean missiles have two names–one designated by Pyongyang and the other by the United States. For instance, the new ICBM is referred to as the KN-20 by the U.S. Pentagon, but Pyongyang calls it the Hwasong-14.

It is believed to be a two-staged, liquid-fueled version of the Hwasong-12, otherwise known as the KN-17. The Hwasong-12 is a single-stage, liquid-fueled intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) that was first tested in May 2017 to a range of around 4,500 kilometers.

Another notable difference is that the Hwasong-12 is outfitted with four Vernier thrusters for stability and guidance. Based on imagery from the July 4 test, it is believed the Hwasong-14 is outfitted with retrograde rockets on the first and second stages, which are used to decelerate the missile stage during separation. Retrograde rockets are essential to multi-stage designs because they ensure the multiple stages do not collide with each other.

Juxtaposing the two models’ delivery systems shows a noteworthy similarity, a welcomed one to U.S. officials. The Hwasong-14 also is believed to require a transporter-erector vehicle, though it is launched from a detachable platform on a concrete pad. That limits the number of launch locations Pyongyang can choose from to pre-sited and pre-constructed launch pads, and likely increases the time needed to launch either.