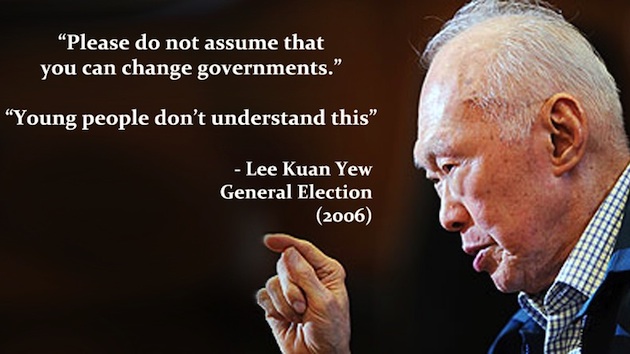

Lee Kuan Yew, prime minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990.

It is not often that the leader of a small city-state — in this case, Singapore — gets an international reputation. But no one deserved it more than Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of Singapore as an independent country in 1959, and its prime minister from 1959 to 1990. With his death, he leaves behind a legacy valuable not only to Singapore but to the world.

Born in Singapore in 1923, when it was a British colony, Lee Kuan Yew studied at Cambridge University after World War II, and was much impressed by the orderly, law-abiding England of that day. It was a great contrast with the poverty-stricken and crime-ridden Singapore of that era.

Today Singapore has a per capita Gross Domestic Product more than 50 percent higher than that of the United Kingdom and a crime rate a small fraction of that in England. A 2010 study showed more patents and patent applications from the small city-state of Singapore than from Russia. Few places in the world can match Singapore for cleanliness and orderliness.

This remarkable transformation of Singapore took place under the authoritarian rule of Lee Kuan Yew for two decades as prime minister. And it happened despite some very serious handicaps that led to chaos and self-destruction in other countries.

Singapore had little in the way of natural resources. It even had to import drinking water from neighboring Malaysia. Its population consisted of people of different races, languages and religions — the Chinese majority and the sizable Malay and Indian minorities.

At a time when other Third World countries were setting up government-controlled economies and blaming their poverty on “exploitation” by more advanced industrial nations, Lee Kuan Yew promoted a market economy, welcomed foreign investments, and made Singapore’s children learn English, to maximize the benefits from Singapore’s position as a major port for international commerce.

Singapore’s schools also taught the separate native languages of its Chinese, Malay and Indian Tamil peoples. But everyone had to learn English, because it was the language of international commerce, on which the country’s economic prosperity depended.

In short, Lee Kuan Yew was pragmatic, rather than ideological. Many observers saw a contradiction between Singapore’s free markets and its lack of democracy. But its long-serving prime minister did not deem its people ready for democracy. Instead, he offered a decent government with much less corruption than in other countries in that region of the world.

His example was especially striking in view of many in the West who seem to think that democracy is something that can be exported to countries whose history and traditions are wholly different from those of Western nations that evolved democratic institutions over the centuries.

Even such a champion of freedom as John Stuart Mill said in the 19th century: “The ideally best form of government, it is scarcely necessary to say, does not mean one which is practicable or eligible in all states of civilization.”

In other words, democracy has prerequisites, and peoples and places without those prerequisites will not necessarily do well when democratic institutions are created.

The most painful recent example of that is Iraq, where a democratically elected government, set up by expenditure of the blood and treasure of the United States, became one of the obstacles to a united people with the military strength to protect itself from international terrorists.

In many parts of the Third World, post-colonial governments set up democratically made sure that there would be no more democracy that could replace its original leaders. This led to the cynical phrase, “one man, one vote — one time.”

Democracy can be wonderful as a principle where it is viable, but disastrous as a fetish where it is not.

Lee Kuan Yew understood the pitfalls and steered around them. If our Western advocates of “nation-building” in other countries would learn that lesson, it could be the most valuable legacy of Lee Kuan Yew.

Thomas Sowell is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305. His website is www.tsowell.com.

The most damning journalistic sin committed by the media during the era of Russia collusion…

The first ecological study finds mask mandates were not effective at slowing the spread of…

On "What Are the Odds?" Monday, Robert Barnes and Rich Baris note how big tech…

On "What Are the Odds?" Monday, Robert Barnes and Rich Baris discuss why America First…

Personal income fell $1,516.6 billion (7.1%) in February, roughly the consensus forecast, while consumer spending…

Research finds those previously infected by or vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 are not at risk of…

This website uses cookies.