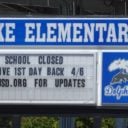

More than half of Illinois’ largest cities are shrinking. Out of the state’s largest 27 cities, 17 shrank in population and 10 grew from 2013 to 2014. (Photo: Rebooting Illinois)

The population of New Orleans fell 7.3 percent after Hurricane Katrina, but guess what. NOLA now has 40,000 more college graduates than before the disaster.

From 2000 to 2013, Detroit lost over 160,000 residents but amazingly added nearly 167,000 college graduates.

It’s an urban myth that population loss and brain drain go hand in hand. On the contrary, of the 100 largest American metropolitan areas that lost population in this time period, every one gained in the percentage of college-educated residents. Such findings are contained in a report from the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank that studies urban issues.

In some, cities with major population losses actually saw their college-educated head count rise to exceed the national average. “Buffalo and Cleveland went from less educated than America to more educated than America,” Aaron Renn, a senior fellow at the institute, told me.

The Winston-Salem metro region, in North Carolina, lost jobs in this period (though not population), in good part because of a declining textile industry. But its number of college graduates grew by an astounding 66 percent.

This bright bit of news should not obscure the serious and enduring problem of poverty in New Orleans, Detroit and other shrinking cities, especially among African-Americans. Their list of challenges remains long, Renn said, but “losing brains is yesterday’s problem.”

Why do so many think otherwise? The public tends to view a city’s talent pool like water in a bathtub. As population declines, educated people do leave; they go down the drain, so to speak. But this misses the running tap at the top of the tub. Educated people also arrive.

There are several reasons for this growth in educated urban residents. Obviously, the general rise in the number of Americans obtaining college degrees plays a part.

Still, why are they disproportionately living in cities once given up for dead?

It happens that many of these cities enjoy the added advantage of being anchored by venerable institutions. Cleveland, for example, has the world-renowned Cleveland Clinic medical complex. Pittsburgh is home to Carnegie Mellon University, a stronghold for science and technology.

Buffalo is an especially interesting case. It lacks big-name institutions but has a huge number of colleges. Many of their graduates stay in town.

Did you know that Buffalo last year had the lowest out-migration rate of any city in America? It also has the highest percentage of people living in the state where they were born; 81 percent were born in New York.

It may surprise many to learn that some cities with the most robust economies are actually experiencing a net out-migration of people with college degrees. New York and Boston are two examples. But that’s no cause for panic. No one is worrying about the future of New York or Boston.

And what about the “cool” factor, the great old architecture and downtowns so appealing to creative types? Renn downplays the importance of hipster enclaves. Cleveland, for example, added about 4,000 people to its downtown from 2000 to 2010. That’s good but not a huge number.

A more positive description would be “nascent repopulation.” That’s a great start.

Your author differs with the Manhattan Institute on a number of other fronts, but these market-oriented researchers have it straight on how hurting cities should direct their resources. They should spend money on improving the infrastructure they already have in place — the roads, pipes, housing. An advantage old urban cores have over new mushroom cities is they don’t have to build these expensive services from scratch.

Above all, turn the public schools into centers of educational excellence and bingo. The educated middle class will stay put, and the poor will move on up.