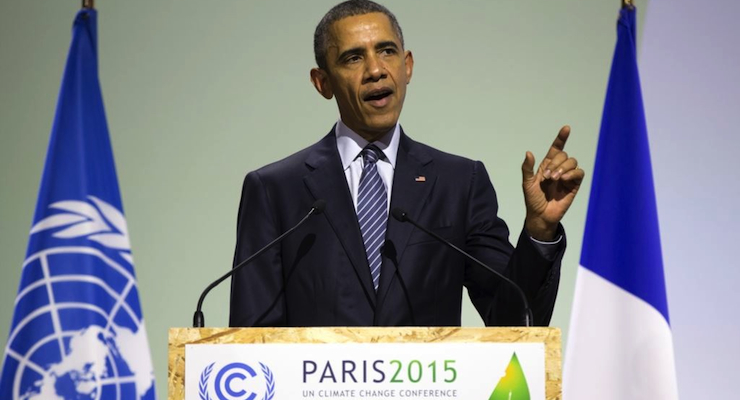

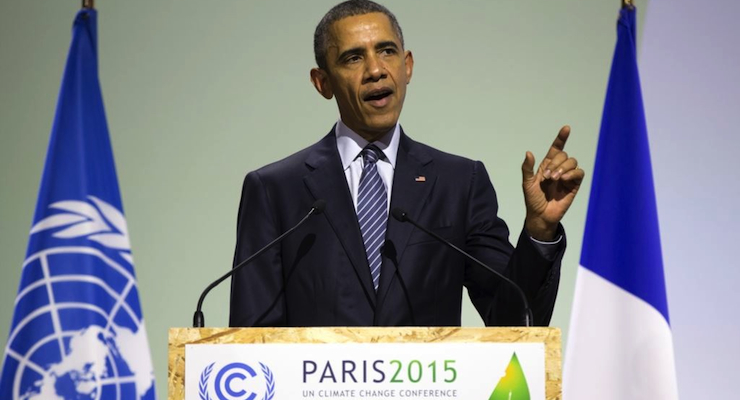

U.S. President Barack Obama speaks at the Paris Climate Change conference on Nov. 30, 2015. (Photo: AP)

“This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” Those were Winston Churchill’s words of battle-weary comfort when World War II started decisively shifting in the Allies’ favor.

They could also be applied to the climate change accord just reached in Paris — 196 countries all agreeing to cut or limit greenhouse gas emissions. The long slog to slow global warming and avoid its worst environmental, economic and security consequences is hard and often thankless political work.

Republicans running for president are obviously not keen on picking up that shovel. They treat the issue as not a problem, a problem for others to solve or unsolvable. Ted Cruz: “Climate change is not science. It’s religion.” Donald Trump: “I don’t believe in climate change.” Ben Carson at least concedes its existence but says that there is “no overwhelming science” that humans are involved.

It may be true that the electorate is focused on the more immediate and dramatic threat of terrorism, and not just Republicans. Global warming can seem boring by comparison.

But terrorism was pretty much ignored until Sept. 11, 2001. Then disaster struck domestically, and the public erupted. Trying to prevent the awful things from happening in the future is what mature leaders do. Sadly, their efforts go largely unappreciated by a public too busy or detached to take notice.

It would be unfair to paint all Republicans as limp on climate change. A survey released in September found that 54 percent of self-described Republican conservatives believe that climate change is happening and that humans play a part in it. Only 9 percent don’t think the planet is warming. (Other polls show far lower levels of concern among Republicans, it must be noted.)

The survey was ordered by Jay Faison, a wealthy Republican from North Carolina determined to sell his party on the need for confronting climate change. Faison created a group called ClearPath to frame the issue in conservative terms.

Its website rumbles against government efforts, such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan. But it promotes the solar boom, noting that from 2010 to 2014, the price of solar energy dropped 50 percent. That’s something conservatives, liberals, libertarians, independents and Whigs would all applaud.

And some of the ideas are quite interesting. The survey found that 54 percent of conservative Republicans would support a tax on carbon if the money collected were rebated. A tax on carbon is a solid way to discourage use of fossil fuels.

Climate change activists criticized the Paris agreement as too little too late. They are correct that it’s not a cure. (Even if the promises are kept, the Greenland ice sheets, for example, probably will remain perilously close to collapsing.)

What the agreement could do, though, is make the bad things happen more slowly and perhaps buy time. And it will give a boost to the good developments — improvements in green energy technology, conservation and the very exciting field of “negative emissions” technology (taking planet-warming gases out of the air).

Here’s where American ingenuity can save the world and make big money at the same time. That’s a conservative talking point, free for the taking.

Think Churchill. The agreement is not the end of the problem. But it’s a lot better than inadequate. It gives hope that something resembling victory is possible. A sense of futility makes people not want to try. Churchill’s brilliance was giving people optimism without sugarcoating the work ahead.

So think “end of the beginning.” The struggle to avoid the most frightening results of global warming has just begun in earnest.