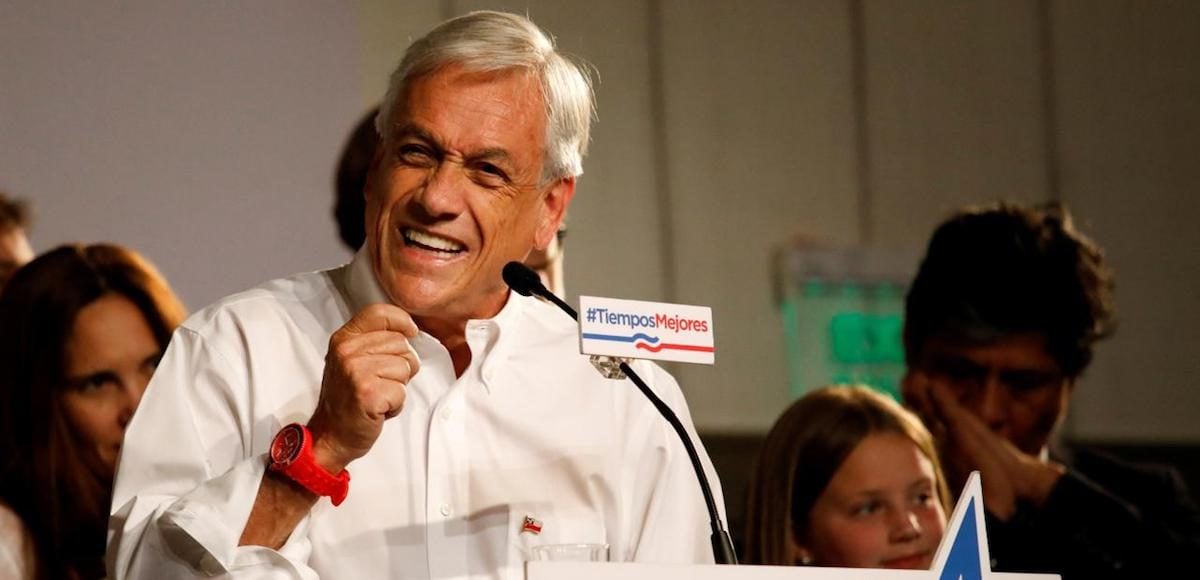

Chilean presidential candidate Sebastian Pinera delivers a speech to supporters after leading in the first round of general elections in Santiago Chile November 19, 2017. (Photo: Reuters)

One of the interesting things I’ve noticed in my world travels is that supporters of free markets and small government generally are known as “liberals” everywhere other than North America. I think the rest of the world has the right idea. After all, folks like Adam Smith are considered “classical liberals,” so it’s bizarre that “liberal” now is used to describe anti-capitalists in America.

To muddy the waters even further, it’s not uncommon for modern supporters of capitalism to be called “neoliberals,” though I wonder if that’s supposed to a be a term of derision.

To muddy the waters even further, it’s not uncommon for modern supporters of capitalism to be called “neoliberals,” though I wonder if that’s supposed to a be a term of derision.

When I’m called a neoliberal in other countries, it’s always by someone who is criticizing my support for economic liberty.

Professor Dani Rodrik of Harvard, in a column for the U.K.-based Guardian, is not a fan of neoliberalism. He acknowledges that the term is ill-defined, but recognizes that it means a less power for government.

…neoliberalism…denotes a preference for markets over government, economic incentives over cultural norms, and private entrepreneurship over collective action. …The term is used as a catchall for anything that smacks of deregulation, liberalisation, privatisation or fiscal austerity.…That neoliberalism is a slippery, shifting concept, with no explicit lobby of defenders, does not mean that it is irrelevant or unreal. Who can deny that the world has experienced a decisive shift toward markets from the 1980s on? Or that centre-left politicians – Democrats in the US, socialists and social democrats in Europe – enthusiastically adopted some of the central creeds of Thatcherism and Reaganism, such as deregulation, privatisation, financial liberalisation and individual enterprise?

Rodrik then proceeds with a lengthy discussion of the weaknesses and limitations of conventional economic analysis.

Much of what he writes is perfectly reasonable. The economy is not a machine and people are not robots, so mechanistic economic concepts – while useful – have limited value. Moreover, culture and institutions make a big difference, and it’s rather difficult to capture those concepts in economic models.

Moreover, he makes some interesting observations on how various nations such as China have liberalized in ways that defy easy analysis.

That is certainly a fair point.

But then he finishes up his column with two examples that simply don’t make sense.

First, Rodrik cites Mexico as a supposed example of neoliberal reform.

Following a series of macroeconomic crises in the mid-1990s, Mexico embraced macroeconomic orthodoxy, extensively liberalised its economy, freed up the financial system, sharply reduced import restrictions and signed the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta). These policies did produce macroeconomic stability and a significant rise in foreign trade and internal investment. But where it counts – in overall productivity and economic growth – the experiment failed. Since undertaking the reforms, overall productivity in Mexico has stagnated, and the economy has underperformed even by the undemanding standards of Latin America.

My reaction is “huh?”

I spend a lot of time combing through international data in hopes of finding success stories to publicize and I’ve never come across anything to suggest Mexico is a good example. Instead, I found evidence a few years ago suggesting the country is a bad example.

Here’s the Mexican data from Economic Freedom of the World. You can certainly argue that Mexico did some good reforms in the late 1980s. But where’s the evidence for sweeping liberalization after the mid-1990s?

There was a very slight increase in Mexico’s score after 1995, which is better than nothing. But I’m not surprised that it didn’t yield impressive results since the rest of the world was liberalizing at a much faster rate.

Indeed, Mexico dropped from #49 to #69 between 1995 and 2000 because other nations were the ones with “extensive liberalization,” not Mexico.

Second, he takes a shot at Chile.

Chile’s neoliberal experiment eventually produced the worst economic crisis in all of Latin America.

“Huh?” would be an understatement. I was flabbergasted by this assertion.

But not the first part of that sentence. He’s correct that Chile is a poster child for market-friendly reform.

Here’s a chart from Economic Freedom of the World showing how the nation’s score dramatically improved between 1975 and 1995.

But I was shocked by the second part of the sentence. Chile had “the worst economic crisis in all of Latin America”?

Since I’ve written several times about the Chilean economic boom, I was totally baffled. What was Rodrik talking about?

So I took another look at a couple of sources to see if I had overlooked something.

Here’s the IMF data on per-capita GDP for Chile and the rest of Latin America. The numbers are only available back to 1980, but everything we see underscores my argument that Chile is a great success. It used to have living standards only slightly higher than the average for Latin America and now the people are more than twice as rich as their peers. If that’s a “worst economic crisis,” we should all be lucky enough to have similar problems.

Then I looked at the Angus Maddison dataset, which allows us to go back to 1970.

His numbers are adjusted for inflation, so the lines don’t rise as rapidly, but we see the same long-run pattern. Chile is getting richer at a much faster pace than other countries from Latin America. Once again, if this is a “crisis,” other nations should hope for a similar fate.

So what did Rodrik mean by “worst economic crisis”?

His article doesn’t provide any details, but if you look at the Maddison data for the early 1980s, there was a downturn, with per-capita output dropping in Chile from about $6,000 to about $5,000. And that reduction was noticeably larger than the average reduction for the rest of Latin America.

I’m guessing this is the supposed “crisis” that he mentions in the article.

But if that’s true, he’s guilty of an egregious example of “cherry-picking” data. Sort of like saying the record-setting 1998 Yankees were a failure because of a four-game losing streak in late August that year.

Honest analysis requires a look at the overall record, and all data sources show that Chile’s economic performance is far superior to its peers.

The bottom line is that Rodrik is on solid ground when he points out the limitations of conventional economic analysis. But when he then decides to criticize pro-market reforms, he concocts two examples that are – at best – sloppily inaccurate.