Since the end of World War II, U.S. foreign policy has been predicated on liberal internationalism’s view that holds exporting economic opportunity will increase stability in the world. During the Clinton Administration, much of this internationalist view was put into practice, breaking from the traditional tie that connects liberalism with the policy of détente pursued during the Nixon Administration.

Both détente and engagement consist of open dialogue, but the liberal internationalist policy of engagement cedes economic power to state actors in the hope that economic interdependence will reduce the potential for conflict. Further, they view this process as a necessary means to push nation-states closer to democratization, which they view as inevitable as economic prosperity grows.

Clearly, and I contend, a simple observation of Americans’ views of China over time represents a rejection of liberal internationalist theory by American citizens. In fact, even though they view it beneficial in theory, in reality they become ever-skeptical and ever-concerned when economic growth threatens to surpass the economic power of the United States.

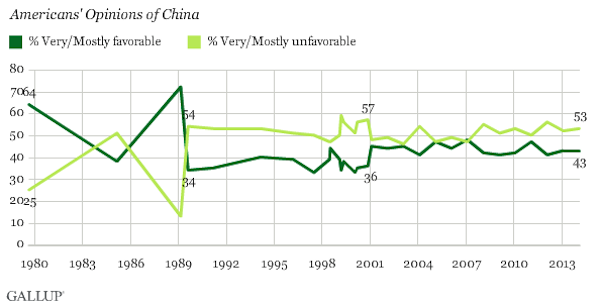

Though Gallup was not yet asking the question when headlines read “Nixon Goes To China,” most security experts agree Americans views of China turned positive after Nixon recruited them as a vital ally against their former-red ally, the Soviet Union. In 1979, when Gallup first asked, 64 percent of Americans saw China favorably, with just 25 percent having a “Very/Mostly unfavorable” view of the emerging Asian power.

After Tiananmen Square, Americans’ favorable view of China bottomed out at 34 percent late. (Gallup)

Following the incident at Tiananmen Square in 1989, Americans’ view of China bottomed out dramatically to 34 percent. The Clinton foreign policy of engagement seemed to have an indifferent and immeasurable impact on public opinion. Even though China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, the steps taken by both the U.S. and China to ensure they could join the international organization occurred under Clinton.

Ironically, the economic gains made from the policy of expanded free trade are precisely what are now fueling the negative perceptions toward the country.

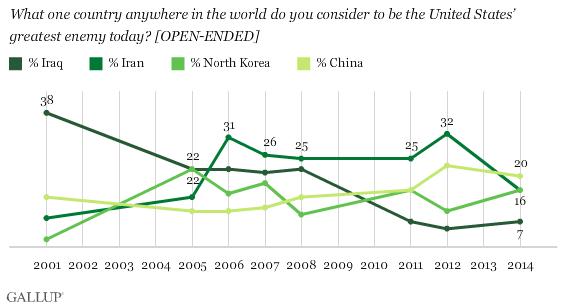

First, let’s look at the list of nations that Americans consider to be the top enemies of the U.S., then compare the trend to the question of who Americans believe to be the leading economic power. Seemingly unrelated, I know, but bare with me on this.

Americans’ view on China has only slightly increased, following a similar pattern as their views on economic power. But Iran has plummeted, thrusting China to number one. (Gallup)

When we look at this time period, we must take into consideration that the “War on Terror” was in full force. As a native North-easterner, I cannot stress enough how much views were impacted by the current events. Nevertheless, we still see the usual suspects up above China until 2003, which suggests Americans base their view not on a nation’s intention, but whether or not they perceive that nation to have the power to project those intentions.

Strengthening my argument, we can clearly see China increase on the enemy list when the financial crisis hit.

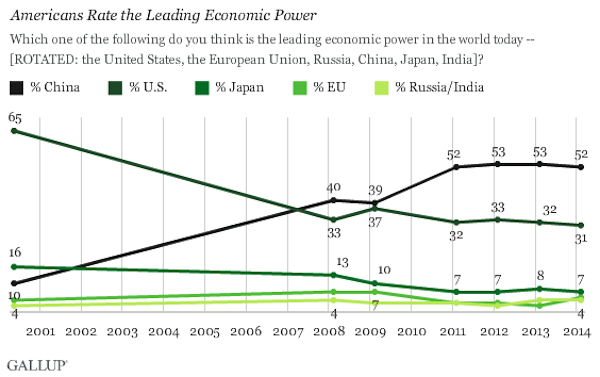

The U.S. still boasts a GDP almost twice that of China, but the majority of Americans (52 percent) believe China is the world’s leading economic power. (Gallup)

Americans have steadily and increasingly become aware of China’s economic power potential, recognizing economic power as a prevailing security threat. Despite headlines being filled with new China military technologies, Americans are more concerned with China’s economic power. Whether or not that is because Americans understand economic power is necessary in order to have military power, is doubtful. I would argue, however, that Americans generally understand that if you want nation-states to do what is in our interests, then you must be perceived as having a dominant economic position.

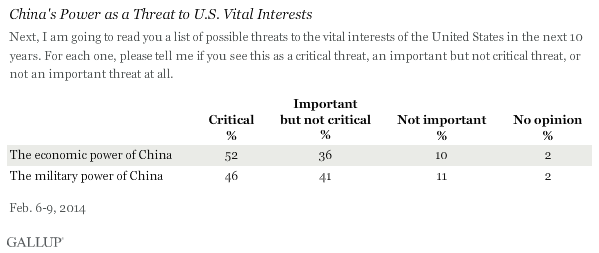

Americans are more likely to perceive China’s economy (52%) than its military (46%) as a “critical” threat to U.S. vital interests over the next 10 years. (Gallup)

When asked, Americans view China’s military strength and economic power as a threat to the vital interests of the U.S., but economic power is more concerning. While at first glance it may sound pretty straightforward, but this truly represents a complete rejection of liberal internationalist theory.

The entire purpose behind international organizations and exporting wealth is to stabilize the world politically, thus reduce the potential for war. But, in reality, economic threats are viewed more concerning than military threats by the American people. Public perceptions regarding security competition inevitably leads to nationalism, even hyper-nationalism, which then leads to a greater propensity for conflict.

With new China policy displaying an increasing dissatisfaction with the status quo in the Pacific, most recently in the form of establishing air defense zones, the potential for international crisis is growing. This past weekend, the first U.S. military boots hit central Thailand soil to kick off the official change in military and foreign policy, known as the Asia pivot.

Operation Cobra Gold, as it was dubbed, didn’t go over well in Beijing or the various state-run news agencies. Xinhua News, China’s People Daily and the China Perspective, all have been attempting to tap into Chinese nationalism for the obvious reasons I just stated above. Unfortunately, the new China looks a lot like the old China, with a large faction favoring regional hegemony. Though Gallup last year found that most Americans regarded China as more friend than foe, opinions will drastically change as U.S. economic power continues to wane and China continues to pursue regional hegemony.

The data above clearly suggest this unfortunate trend will continue. Abandoning the impractical liberal internationalist theory of foreign policy, altogether, would lead not only to a more coherent U.S. foreign policy, but the stabilization of U.S. views toward enemy and friend nations, whether for better or worse.