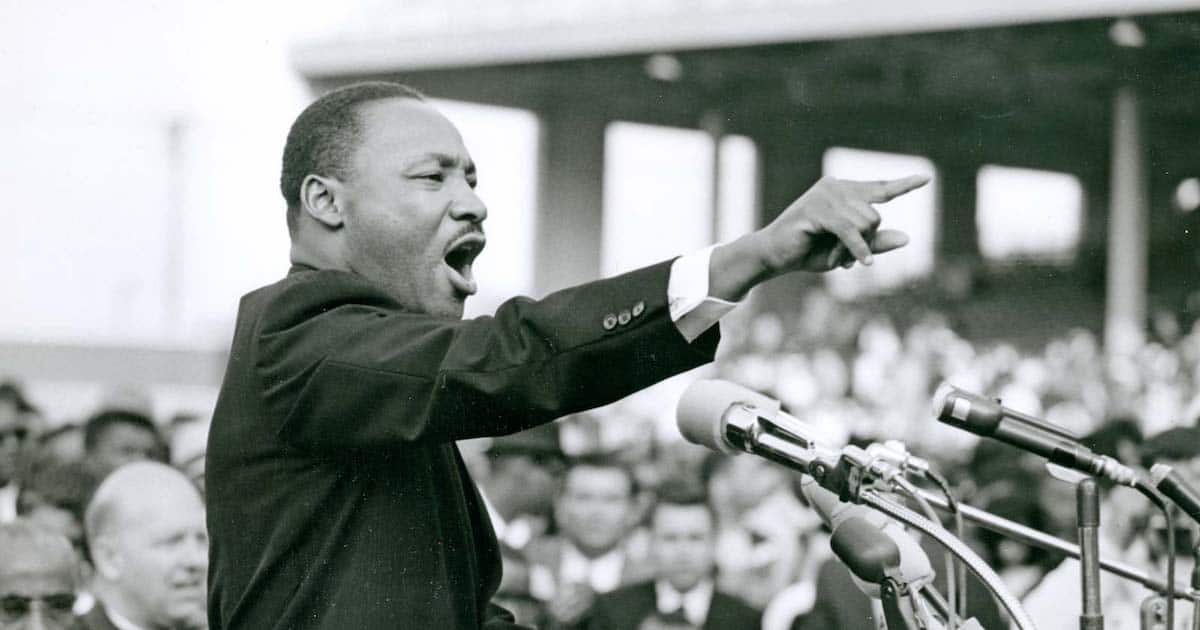

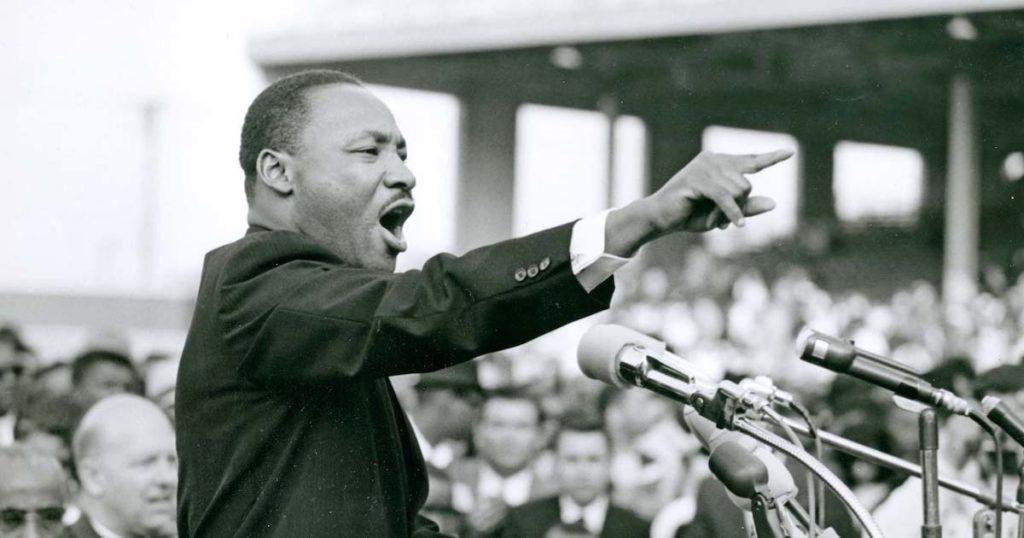

Martin Luther King Jr. and His Tactics Weren’t Widely Supported Before Assassination in 1968

On Monday, Americans honor the memory of the peaceful civil rights leader who was born on January 15, 1929, and assassinated on April 4, 1968. While Martin Luther King Jr. is now universally revered, few know he was once widely unpopular.

He only became beloved after his death.

In the 1960s, Gallup gauged Dr. King’s image using a “scalometer” that asked the public to rate their views on him on a +5 to a -5 scale. The historical data show his image became decidedly more negative.

In 1963, Dr. King had a 41% positive and a 37% negative rating, a tenuous margin above water by just 4 points. In 1964, it was 43% positive and 39% negative, again only +4. In 1965, his rating was evenly divided at 45% positive and 45% negative.

Given the large percentages with no opinion, as well as the racial tension at the time, it is almost certain at least some of those negative views were silent.

In 1966—the last time Gallup used the scalometer to measure Martin Luther King Jr.’s image—it was overwhelmingly negative. Less than a third (32%) held a positive view, while 63% were negative. Gallup did not gauge Dr. King’s favorability rating in either 1967 or 1968.

As opposed to other civil rights activists, Dr. King argued for nonviolent action, including mass demonstrations, boycotts and acts of civil disobedience.

Americans praise him for those beliefs now, which he practiced until his assassination in 1969. But like their views on Dr. King, himself, they once held different views.

In 1961, Gallup asked Americans whether tactics such as “sit-ins” at lunch counters, “Freedom Buses” and other demonstrations helped or hurt the chances of racial integration in the South. More than half, at 57%, said they had hurt, while a little more than a quarter, at 27%, said they had helped.

Two years later in June 1963, shortly before the Dr. King’s August 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Gallup asked if “mass demonstrations” were more likely to help or more likely to HURT the cause for racial equality.

Sixty-percent (60%) said mass demonstrations hurt, while 27% believed they helped. Less than a year after Dr. King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech, 74% said these actions hurt and just 16% said they were helpful.

Obviously, Americans would later express more positive attitudes toward nonviolent demonstrations and Dr. King, himself. By May 1969, 63% said black Americans could win civil rights using nonviolent demonstrations.

In 1999, 49% of Americans said Mother Teresa was “one of the people I admire most” from the 20th century. Martin Luther King Jr. was second with 34%, ahead of John F. Kennedy, Albert Einstein, Helen Keller, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Billy Graham, Pope John Paul II, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill.

In life, he appeared on the Gallup Top 10 Most Admired List in 1964 (#4) and 1965 (#6).